Policy Entrepreneurship

Each problem that I solved became a rule, which served afterwards to solve other problems.

— René Descartes

The Challenge

Misconceptions about how policy change happens mean most people underinvest in policy agenda-setting

Most technical experts underinvest in policy agenda-setting, treating the government as a black box that requires significant funding and expertise to influence. Common myths include:

Policy change requires legislation. In reality, executive actions can be equally impactful. For example, a new USCIS rule led to a 30% increase in O-1 visa use.

You need to be a donor to influence policymakers. In reality, policymakers rely on academia and civil society to provide ideas and outside support for their goals. For example, through agenda-setting papers and technical assistance, a small group of motivated individuals established ARPA-H with a $3 billion budget.

Policy campaigns are resource-intensive. In reality, if you are able to identify a window of opportunity, a modest investment of time and resources can make a substantial difference. This is especially the case if a policy proposal will not trigger ideological opposition or opposition from entrenched interest groups.

The Play

The presence of effective policy entrepreneurs working on a problem can have a meaningful impact on policy outcomes

Policy entrepreneurs are able to identify the right policy lever to make progress on a problem, develop the documents needed to instantiate their idea, find and recruit allies, and leverage key dates on the calendar to make progress.

Having an agenda.

Policy entrepreneurs are able to provide detailed answers to questions like:

What am I trying to get done? What is the status quo? What is a more desirable future in the issue area that I care about?

How will my project get done? What public and private actions or resources are needed to achieve my goals?

How will I know if my idea is successful?

What metrics of success can be tracked over time?

Why do I believe this is the right thing to do, and that doing A will (or is likely to) cause B to occur?

Whom do I need to convince of the value of my idea? Who should be involved in its implementation?

How do I communicate the essence of my idea to a non-expert?

Creating the documents that are necessary for a policy to be considered and implemented.

It’s likely that, at some point in the process, policymakers will need to draft one or more documents in order to make and implement a decision.

Policy entrepreneurs know that part of moving a decision forward is to first discover what document (or documents) need to be written so the policy can be implemented. What they’re trying to do will determine the appropriate policy lever. For example, developing a regulation like the International Entrepreneur Rule requires publishing a draft in the Federal Register, collecting public comment, and finalizing a rule that goes into the Code of Federal Regulations. If the policy entrepreneur is trying to launch a multi-agency research initiative, it may require a request for proposals that’s embraced by multiple agencies and an inter-agency memorandum of understanding that allows any one of those agencies to fund submitted proposals. If the goal is to send a clear signal that something is a presidential priority, then issuing a presidential memorandum or executive order can help accomplish that. These documents also generally direct one or more agencies to take some concrete action.

Other documents useful in the development and implementation of policy include legislative text, funding proposals for the president’s budget, a proposal to hold a presidential event, amicus briefs on important cases, administration policy statements on proposed legislation, agency directives, fact sheets and other event press releases, and memoranda of understanding between agencies or with outside organizations.

While not all policy goals can be accomplished through documents alone, they are critical in framing a challenge or opportunity, presenting options, making a decision, and implementing that decision.

Documents, like draft rules for public comment in the Federal Register, can advance a policy idea | U.S. Government Printing Office

Finding allies.

Policy entrepreneurs are able to find people with shared interests who can help them get the job done. They think about people with specific skill sets whom they could recruit to support their effort. They develop and manage a network of allies with aligned interests, such as:

Idea people, especially those with specific ideas on “what, how, and who” and who are willing to commit them to paper;

Special assistants, chiefs of staff, gatekeepers, and schedulers for key principals;

“Doers” who follow up when they agree to do something;

Opinion-makers, key media contacts, and people with a large following;

Foundation staff and executives; and

Intermediary organizations that (a) can help you engage in wholesale rather than retail efforts at coalition-building; (b) are trying to scale-up an intervention that the administration supports.

In particular, policy entrepreneurs heed the maxim, “find your doers.” Doers are energetic and entrepreneurial people who take responsibility for the execution of an idea, even if important elements of the process are outside their job description. If they get stuck, they are willing to explain why and what help they need.

Making the schedule their friend.

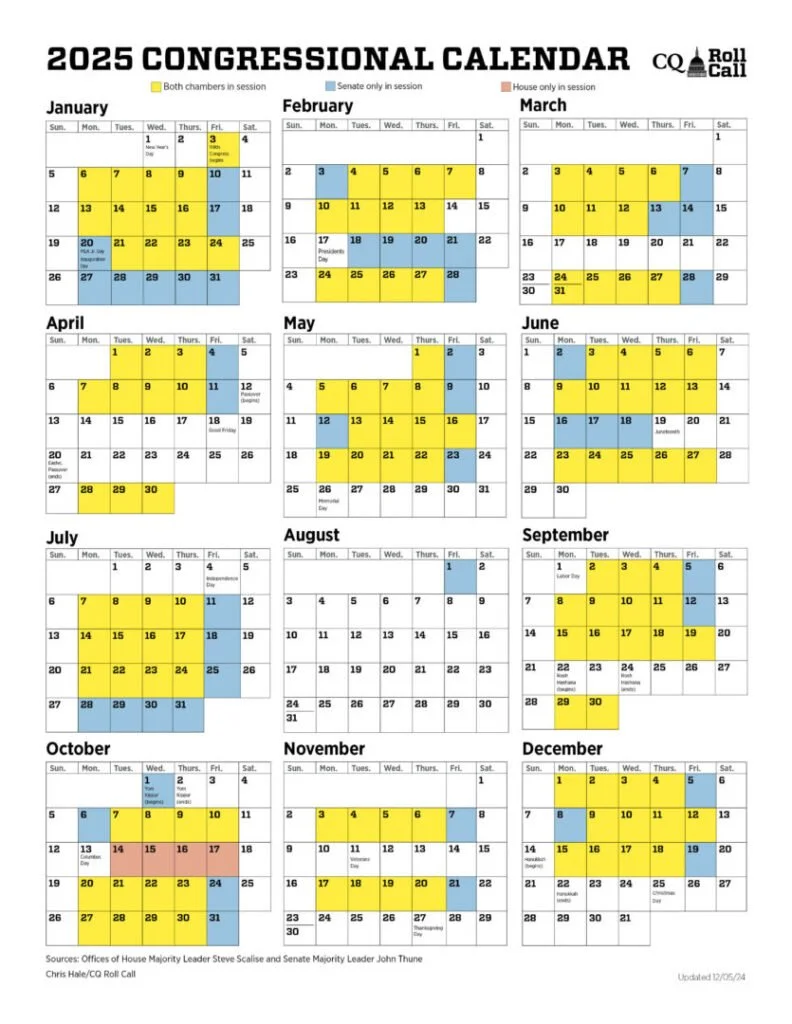

Policy entrepreneurs have a keen awareness of the calendar and are often working backwards from a key date or milestone. For example, every year, typically in January or February, the President gives a State of the Union Speech where they highlight the administration’s priorities.

There are many other examples like SOTU, such as the annual National Defense Authorization Act, the formation of the President’s budget, and the annual appropriations process. Policy entrepreneurs are aware of and as a result capable of leveraging these deadlines to advance their ideas.

Policy entrepreneurs can leverage schedules to capitalize on windows of opportunity | CQ Roll Call

Having a large and growing toolbox.

Policy entrepreneurs must be able articulate a coherent relationship between means and ends. They also need to identify the policy levers that will help achieve a given goal, such as changes in the tax code, regulatory policy, legislation, R&D investments, etc.

How to support policy entrepreneurs

Philanthropists can support technical experts in their area of interest who have or are motivated to learn the skillsets and mindsets of policy entrepreneurs. There are a number of ways to do so.

Support tours of duty. Philanthropists can support the placement of talent into congress via fellowships administered by external entities, such as professional societies (e.g. AAAS), universities, and nonprofits (e.g. Horizon Institute for Public Service). Congressional fellows are paid through stipends provided by their sponsoring organizations and are treated as temporary congressional employees under relevant statutes.

Train subject matter experts on skillsets and mindsets of policy entrepreneurship. Philanthropists can support programs to help subject matter experts become more effective policy entrepreneurs. For example, the Aspen Policy Academy offers policy entrepreneurs support in the form of resources, workshops, and networking events.

Capture tacit knowledge of civil servants and political appointees. Philanthropists can support programs to capture the learnings of civil servants and political appointees. Many policy entrepreneurs are so absorbed in the daily work of getting things done that they don’t take the time to document what they did and how they did it. For example, launched by the Policy Entrepreneurs Network (PEN) and the Institute for Progress, Statecraft is a newsletter which interviews policymakers on how they got something done.

Policy readiness levels

Effective policy entrepreneurship rests on spotting policy windows. NASA and the Defense Department use a technology readiness level to assess the maturity of a technology – from basic research to a technology that is ready for deployment. Policy entrepreneurs can similarly develop the “policy readiness” of an idea by taking strategic action to increase a proposal’s chance of success.

Policymakers are often time constrained, and therefore more likely to consider proposals that have anticipated the questions raised by the policy process. These include:

1. What is a clear description of the problem or opportunity?

2. What is the case for policymakers to devote time, energy, and political capital to it?

3. Is there a credible rationale for government involvement or policy change?

Economists have developed frameworks for both market failure (such as public goods, positive and negative externalities, information asymmetries, and monopolies) and government failure (such as regulatory capture, the role of interest groups in supporting policies that have concentrated benefits and diffuse costs, limited state capacity, and the inherent difficulty of aggregating timely, relevant information to make and implement policy decisions.)

4. Is there a root cause analysis of the problem?

Toyota uses the “five whys” framework to prevent superficial or incomplete answers to this question.

5. What can we learn from past efforts to address the problem?

If this is a problem U.S. policymakers have been working on for decades without much success, is there a new idea worth trying, or an important change in circumstances?

6. What can we learn from a comparative perspective?

Have other countries or different states and regions within the United States tried to address the problem?

7. What metrics should be used to evaluate progress? What strategy should policy-makers have for dealing with Goodhart’s Law?

Goodhart’s Law states that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to become a good measure. For example, a police chief under pressure to reduce the rate of violent crime might reclassify certain offenses to improve the statistics.

8. What are the potential policy options, and who needs to approve and implement them?

This question – as is often the case – leads to more questions:

What is the evidence to support each option?

What is the logic model associated with a given option? Why is it likely that a given policy change will have the desired impact?

What policy instrument or instruments are required to achieve the goals associated with the idea? Who would need to act to both approve and implement these policies?

Is it possible to measure the costs and benefits? Some policy fields, such as global health, measure the “outcome per dollar” of different interventions as measured by QALYs (quality-adjusted life-years) saved per dollar.

What is the political and administrative feasibility of a given option?

What are the potential unintended consequences of a policy proposal?

9. What are the documents that are needed to both facilitate a decision on the idea, and implement the idea?

In the U.S. context, examples of these documents or processes include:

Decision memos. These memos typically provide background information on the policy proposal, why a decision is required, the policy options, and the pros and cons of those options.

Executive Orders signed by the President.

Policy guidance provided by one or more agencies, such as the Office of Management and Budget.

Strategy documents that describe how a mix of policy actions is designed to achieve a goal or set of goals.

Budget proposals and Congressional appropriations.

Legislation or legislative amendments.

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for regulatory actions.

A charter for an inter-agency working group.

Job descriptions for efforts to recruit people with important skills to the public sector.

A “request for proposals” for competitively-allocated funds for grants and contracts.

Rules for an incentive prize, Advance Market Commitment, or other market-shaping intervention.

Descriptions of “commitments to action” from companies, non-profits, universities, philanthropists and foundations, state and local governments, investors, etc.

What legitimate concerns have been raised, and what are potential responses to these concerns?

To the extent that there are significant disagreements about those ideas, why might people and stakeholders disagree? This might be different interpretation of data, different views about whether a given policy proposal is likely to be effective, ideological disagreements, or divergent interests.

Are there creative ways to reconcile differences of opinion and interests?

10. Has the idea been reviewed and critiqued by experts, practitioners, and stakeholders? Is there a coalition that is prepared to support the idea? How can the coalition be expanded?

11. How might tools such as discovery sprints, human-centered design, agile governance, and pilots be used to get feedback from citizens and other key stakeholders, and generate early evidence of effectiveness?

12. What steps can be taken to increase the probability that the idea, if approved, will be successfully implemented?

For example, if you were a speechwriter, what stories, examples, quotes, facts and endorsements would you use to describe the problem, the proposed solution, and the goal? What are the questions that reporters are likely to ask, and how would you respond to them?

13. How can the idea be communicated to the public?

For example, this might involve analyzing the capacity of the relevant government agencies to implement the recommended policy.

Case Studies

Securing the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Act

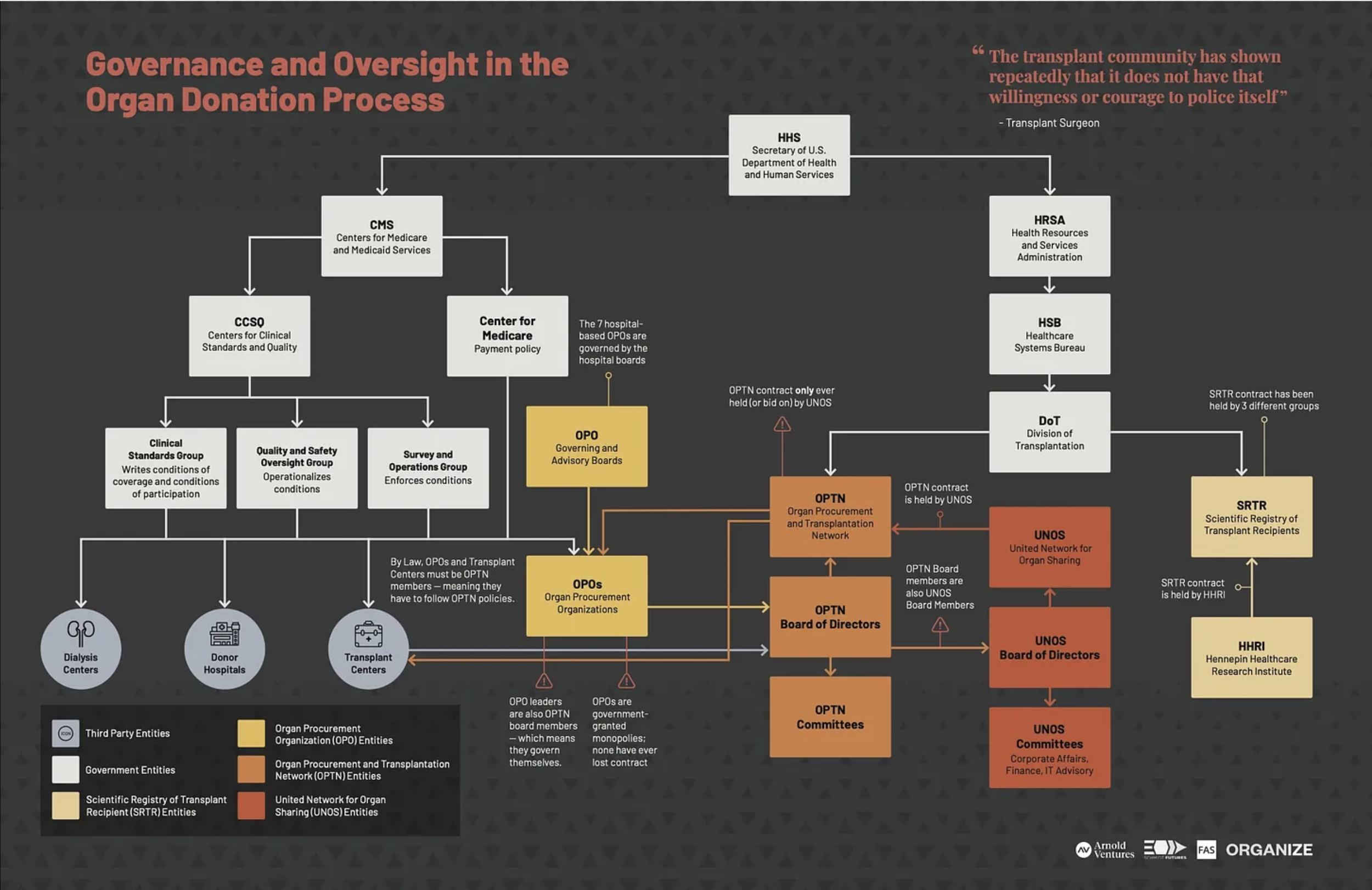

Jennifer Erickson, now a Senior Fellow with the Federation of American Scientists, and Greg Segal, founder and CEO of the nonprofit Organize, observed an urgent need to tackle deficiencies and a lack of oversight in the U.S. organ transplant system.

Together, they advocated to overhaul a monopoly contract held by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) over the management of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Using data that Greg and his team gathered, which highlighted that more than 28,000 organs were going unrecovered yearly, Jennifer and Greg were able to build a national case for reform.

Through targeted outreach, Jennifer and Greg raised national awareness around the issue and engaged stakeholders across the government, including the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, where Jennifer previously worked. Greg also explains how strategic framing has been key in his efforts:

One percent of the entire federal budget goes to dialysis. So we started foregrounding kidneys in our advocacy, but reform to the kidney donation system, at least the deceased donation system, is a vehicle for the same reforms for all of the organ categories. After we started talking about the importance of helping people get kidney transplants, within a year or two, there was a presidential directive on reforming the organ donation system that rode on the Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health.

Driven in part by advocacy efforts from leaders like Jennifer and Greg, the U.S. Digital Service published the report Lives are at Stake, bringing even more attention to issues in the organ procurement system.

The report ultimately led to the passage of Securing the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Act, a bipartisan law removing a decades-old provision in the National Organ Transplant Act that had effectively secured UNOS as a sole contractor. Under the new act, the Health Resources and Services Administration now has the flexibility to contract with multiple organizations to operate the OPTN.

Flowchart showing the governance and oversight structure in the organ donation process | Organ Donation Reform

Opening Veterans’ Access to Health Care

Marina Nitze, now a partner at the Layer Aleph crisis engineering firm, was first engaged in policy as an Innovation Fellow in the U.S. Department of Education, tapped to bring a fresh eye toward streamlining government processes.

When she joined the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as Chief Technology Officer in 2013, the VA was dealing with a severe backlog of more than 800,000 healthcare applications and a reputation for slow-moving systems.

Marina began shadowing a veteran and quickly spotted room for major technical fixes to the VA’s fragmented web of forms. Through vets.gov, she introduced a user-friendly platform where veterans could apply for and track all of their benefits. Since building the interface, about 2 million veterans have used it to secure health care.

Apart from her own efforts to speak directly to end users, she also attributes her success revamping the VA to former Secretary Bob McDonald’s championship of data-driven processes:

...he also understood that it was possible to measure consumer experience. That was a lever that had been totally missing. Nobody was measuring anything at all. Sec. McDonald started tying measurements to performance plans. Now your ability to keep your job, get the promotions you want, etc. are all going to be related to improving these customer service numbers.

Beyond vets.gov, Marina is credited with creating Caseflow and the Clinician User Interface, platforms that have streamlined processes for appeals for legal representation and disability compensation claims. She has also been recognized for building the first U.S. Digital Service team within the VA, which leads on bringing digital improvements to overly complex systems for accessing government services.

Veteran tests vets.gov prototype and shares feedback | U.S. Digital Service

How we can help

Renaissance Philanthropy can help philanthropists support policy entrepreneurs in their area of interest We can do this by:

Identifying people with expertise in a relevant area that are interested in becoming policy entrepreneurs;

Designing and implementing fellowship programs;

Democratizing access to the skills needed to be an effective policy entrepreneur by capturing and organizing the tacit knowledge of people who have been effective in government, and

Connecting policy entrepreneurs to allies, and people with specialized expertise (e.g. drafting legislation, designing incentive prizes, etc.).

Resources

Bring On the Policy Entrepreneurs (Issues in Science and Technology)

How to Be a Policy Entrepreneur in the American Vetocracy (IFP)

Increasing the “Policy Readiness” of Ideas (Tom Kalil)

Policy Entrepreneurship at the White House (Tom Kalil)

Statecraft (IFP)

To Speed Up Scientific Progress, We Need to Understand Science Policy (IFP)

Tom Kalil on how to do the most good in government (80,000 Hours)