Scientific Field Creation

The Challenge

Emerging scientific fields face make-or-break challenges during their early development, when key decisions can determine their long-term trajectory. This playbook identifies levers for catalyzing and influencing field creation to increase the likelihood of success and impact.

Field building refers to a process where a set of individuals and organizations work to address a common challenge that is of sufficient magnitude to necessitate a paradigm shift, and their actions unlock a field’s progress for impact at scale. Fields traverse a life cycle with four stages: latency, growth, maturation (or peaking), and institutionalization (or decline).¹ Emerging ideas at the latency stage are ripe for field creation, where the needs may be distinct from those at later stages.

While there are developed field building methodologies in philanthropic circles,¹ ² ³ ⁴ ⁵ it is not well recognized as a practice amongst many traditional scientific practitioners. Scientific field creation – often the earliest stage of field building – presents a strategic leadership opportunity to unlock broader scientific progress and create a foundation for future work. This can be particularly valuable in emerging fields that are high-risk, high-reward, non-traditional, or require a diversity of actors. New scientific fields are ripe for discovery, where there can be “...golden ages, with fundamental questions about the world being answered quickly and easily.”⁶

The Play

Creating a scientific field requires early, intentional investments in three key elements:

Actors: Identify and engage the key stakeholders needed to holistically accelerate progress and foster them to succeed, while recognizing that early actors may play a different role than late actors.

Connective tissue: Activate, build, and nurture an ecosystem centered around a shared knowledge base, with the elasticity to evolve and weather controversy.

Resources: Provide risk-tolerant funding that is responsive to rapidly evolving needs, early experimentation, and offers stability as the field takes shape, particularly while there may be stages with scattered or sporadic impact.

Successful scientific field building can:

Rapidly expand the set of key stakeholders contributing to a field

Enable interdisciplinary progress, because many new fields emerge from the intersection of existing scientific disciplines

Develop a strong, trusted scientific base in emerging areas

Actors

Philanthropists:

There is an outsized role for philanthropists to play in catalyzing the creation of new fields by funding research, leadership development, and field coordination (through direct funding or by supporting intermediaries such as NGOs).⁷

Philanthropists have the power to directly or indirectly shape field direction, framing, and priorities, which may have profound and lasting impact on how emerging work is translated into action.8

Philanthropies are responsible for establishing accountability structures to ensure that their power and influence is wielded for beneficial, responsible outcomes.⁸ For example, establishment of robust research funding oversight processes to ensure that awards are administered ethically.

A diversity of actors contribute to scientific field creation. The movement of actors into or out of a field can be an important signal of both field health and its evolution to different stages of field development.¹

Intermediaries (e.g. NGOs, universities, professional societies):

Intermediaries often fill critical field building roles that range from systems-level catalysts to specialists targeting specific gaps.

Some intermediaries (e.g. NGOs, university research centers) are designed to be short-term scaffolding, where their disappearance signals success; others evolve into long-term infrastructure to sustain the field as it develops and grows.²

Intermediaries can help de-risk early-stage research – doing the research in-house or directly supporting it to be performed externally.

Intermediaries have a unique vantage point where they can apply a “dual lens” that enables focus on both the state of the field and on gaps, blockers, and leverage points that may only be apparent when considered from a systems level perspective.⁹ For example, establishing a new professional society, building a shared facility for expensive equipment, creating experiential learning opportunities for mid-career professionals in adjacent fields, publishing open educational resources, etc.

When funded by philanthropies, NGOs may have strategic direction and priorities that flow down from their funders, transferring direct and indirect power that needs well-defined accountability structures.

A potential NGO pitfall can occur when their mission is too broad, shifting, or loosely defined, leading to diluted impact and strategic drift.¹⁰

Government agencies and policymakers:

In many cases, a field will require activation of government actors, infrastructure, and resources to realize durable impact.

During field creation, governments may have limited interest in or ability to support early, high-risk, controversial research that doesn’t align with their existing portfolios.

Early relationship-building can lay the groundwork for eventual transition from philanthropic funding to government or mixed funding as the field matures and becomes less risky.⁹ Effective early engagement focuses on education, shared knowledge base, and trust-building, not immediate alignment or funding.

Moving too fast can trigger perceptions of recklessness and risks alienation, especially in politically or ethically sensitive areas. Field builders benefit from recognizing existing portfolios, knowledge, and expertise. Establishing a culture of transparency, curiosity, mutual learning, and opportunity enables productive development while navigating unknowns and knowledge gaps that are inherent to any new field.

Venture capitalists (VCs):

VCs can be a powerful force in field creation when emerging ideas have high commercial potential. For example, “modified mRNA as a new kind of medicine” as developed by Moderna, was funded by the VC firm Flagship Pioneering, as well as early funding from DARPA to apply mRNA technology to infectious diseases.¹¹

VCs often have hard-won experience in how to build and scale technology, and how to simultaneously build and scale the company needed to execute such actions. These actions are critical to a scientific field’s ability to graduate from the latency stage into the growth stage.

While VC support is essential for some emerging fields, there are also occasions where VC engagement, particularly at the field creation stage, may be detrimental. There is a “tragedy of the commons” risk where profit incentives may jeopardize credibility and long-term outcomes, in some cases embroiling areas prone to controversy or moral, ethical disagreements. For example, Make Sunsets, a venture-backed climate intervention startup has negatively impacted the credibility of the nascent field of stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) by advancing a profit-driven effort that experts believe is poorly aligned with the scientific, social, and political state of the field.¹² As a counterexample, VC engagement in the carbon removal approach of enhanced rock weathering has advanced scientific learning, by increasing the size and diversity of field trials (see Cascade Climate Case Study for more details on deployment-led learning).

Field builders benefit from strategic analysis of how, when, and if to engage VCs, recognizing that the benefits and risks associated with their early engagement varies depending on the nature of the specific field.

Talent:

Fields at different stages require different types of talent. During field creation, attracting curious, creative, and risk-tolerant researchers is a critical cornerstone for success.

Participation in emerging controversial or high-uncertainty fields may lack incentives or institutional support, and researchers may be reluctant to engage due to peer pressure.

Emerging fields often have few existing experts and benefit from “porous boundaries” that allow entry into the field from adjacent sectors and disciplines, which ideally leads to organic collaboration and unprompted growth of ideas.² ¹³

Constructive skepticism has a valuable role, contributing to the development of a shared identity by helping to sharpen mental models, refine the field direction, and surface hidden assumptions.⁵

Overreliance on a small, tight-knit group can lead to dogmatism or intellectual stagnation. If this happens, the field might become so niche that it fails to achieve broader acceptance, engagement, and impact. Infusion and turnover of talent create resiliency to evolving priorities, funding, and other external factors.⁹

Field builders should invest early in developing a diverse, well-supported talent pipeline. This includes fostering opportunities to engage people in adjacent fields, where there may be opportunities for them to enter the field through peer-review processes or as early contributors.

Considerations include:

Who is included? What are their backgrounds, career stages, geographies, and areas of expertise?

How are they engaged? Are there meaningful opportunities for recruitment, education, and mentorship?

What sustains them? What structures, incentives, and resources will keep them active and supported over time?

Case Study

TIME Initiative: Accelerating Talent in Aging Biology

Aging biology is an emerging scientific field that studies the biological processes that determine how and why aging occurs. By better understanding these mechanisms, researchers hope to slow the progression of age-related diseases and disabilities, with profound public health, quality of life, and economic implications. But despite its promise, the field can be perceived as speculative or sci-fi-adjacent, and has struggled to establish a pipeline for development of early-career researchers. Without deliberate efforts to engage high-potential talent, the field risks stagnation or dominance from rogue actors.

The TIME Initiative, a nonprofit field catalyst and idea incubator, has focused on lowering the barriers for early entry into the field at the undergraduate level, where career trajectories are often shaped. 14 TIME’s strategy combines science-driven education, mentorship, and credibility buffering to help students engage in aging research without fear of reputational fallout.

TIME fills a critical gap: there are currently no undergraduate programs in aging biology. Through targeted fellowships, TIME supports students eager to explore translational, outcome-focused research across multiple dimensions including societal and economic impacts, policy, and communication. This work has activated and accelerated a new generation of aging researchers, with alumni moving on to publish, join relevant graduate programs, and initiate startups.

The TIME Initiative activates early talent and engagement in aging research.

Connective Tissue

In early-stage field creation, connective tissue refers to the infrastructure – formal or informal – that enables actors to coordinate, communicate, and align on strategic priorities.² A key part of this is establishing a shared knowledge base,⁹ reducing fragmentation, and coalescing stakeholders in the identification and development of key initiatives.

Finding a home:

New scientific fields often don’t fit neatly into existing academic journals or conferences. A lack of suitable publication outlets is a structural challenge, forcing pioneers to shoehorn work into traditional disciplines or split interdisciplinary findings into multiple outputs. This can limit the visibility and credibility of emerging fields. A powerful intervention is to seed new journals, special issues, or conference tracks specific to the field. Providing respected venues for publication increases legitimacy and incentivizes researchers to contribute. Recognizing and providing a home for unpublished field-specific outputs (datasets, methods, negative results) is equally important; early-stage fields thrive when contributors are credited for their work, even if it may be atypical or nontraditional. For example, CDRXIV is a repository for preprint articles and datasets associated with the field of carbon dioxide removal.¹⁵ However, there can be a trade-off between directly building new infrastructure versus spontaneous infrastructure formation as a signal of field building effectiveness; strategic infrastructure development can ensure that there is still sufficient signal to measure progress.

Enabling actors:

Early field development requires creative organizational models to bring together a diversity of actors to connect and share knowledge. Philanthropic funders and intermediaries can shape a field’s early direction by supporting and curating intentional convenings, often with outsized implications for the direction and impact of a field.¹ Those who are closest to the work – with the most direct knowledge of challenges and potential solutions – should be included alongside funders, field leaders, and community builders.² Who’s in the room will influence which ideas gain traction and how the field defines itself, building both credibility and community in the process.

Case Study

Renaissance Philanthropy’s ARC Initiative and Climate Emergencies Forum

Catastrophic climate risk sits in a structural gap: the science is advancing quickly, but the surrounding ecosystem is fragmented, intervention-specific, and often dominated by narrow advocacy rather than system-level readiness. Tipping-point researchers, Arctic modellers, national-security planners, Indigenous leaders, funders, and governance actors rarely share a common frame—so early warnings fail to translate into authorised action.

The Advanced Research for Climate Emergencies (ARC) 16 initiative and the Climate Emergencies Forum (CEF) 17 fill the three missing functions required to turn this fragmented landscape into a field. ARC (a program of Renaissance Philanthropy) creates credible R&D anchors: well-designed programmes that define problems, generate early evidence, and give technical shape to the space. The ARC Fund creates a capital architecture: an expert-led, intervention-agnostic pool that can back the most important opportunities across the whole landscape. And CEF builds the ecosystem that those programmes require to succeed. It convenes the right scientific, policy, community, and funding actors; produces shared narratives and synthesis; and forges the coalitions that give early-stage work legitimacy, governance pathways, and real adoption routes.

In combination, ARC and CEF turn a fragmented risk landscape into a coordinated field by pairing programme creation and expert capital with the ecosystem-building needed for legitimacy, governance, and adoption—well before any incumbent institution could assemble these pieces.

Convening format examples

Navigating risk:

Scientific field building – particularly during field creation – face many risks, including:

Cold start and controversy: Many early research fields must overcome “cold start,” building a field in a topic area with few existing experts or resources. This challenge is compounded when an emerging field is also controversial. Controversy can dissuade researchers and funders due to perceived reputational risk, while the lack of credible participants makes the field harder to understand and easier to dismiss. These dual challenges can be mutually reinforcing, locking the field in a cycle of inertia.

Rogue actors: Individuals or entities that are reckless or negligent in their pursuit of new fields can pose a serious risk, especially when their actions – which they may perceive as right or just – are disconnected from credible scientific or social processes. Their involvement can heighten controversy, alienate serious contributors, and in some cases, derail the field entirely.

Pivot penalty: When scientists move from an established research track to a new field there is a “pivot penalty” where the impact of their work drops sharply the further they move from their prior expertise.¹⁸ Additionally, transitioning to a new area of study introduces funding uncertainty which can further disincentivize scientists from shifting tracks. Recognizing this, Schmidt Sciences has created a Polymaths program,¹⁹ which is designed to encourage mid-career researchers to take “adventurous leaps into new research domains, experiment with new methodologies and ideas, and inspire impactful scientific breakthroughs.”

Overcoming these challenges requires action from early visionaries and community builders, who may be researchers with big ideas that haven’t found a home in traditional structures or solution-oriented organizers who can shape the systems level dimensions of an emerging field. Philanthropies and NGOs can be catalytic in activating and supporting these actors, de-risking a pathway for them to be productive and successful in emerging fields. A powerful tool for this is scientific roadmaps, where a diversity of participants co-create analysis, identify knowledge gaps, and establish shared priorities.²⁰ A strong roadmap can serve as a “north star” for the field, lowering barriers to entry and focusing talent and funding around a common direction.

The Role of Roadmapping

Scientific field building is often choked by bottlenecks. Convergent Research explores scientific roadmapping to spur technological advancement.²⁰ A diverse group of participants who think outside the box and are willing to take risks are key to the roadmapping process, where they can identify and tackle tension areas that define a specific problem and topic. The process is not centered on consensus, rather a roadmap emerges from an “amalgam of perspectives” that shapes the field direction, and in some cases may continue to evolve. Agenda-setting manifestos enable greater understanding of the breadth of approaches paired with details on the state of the science (and sometimes governance) of any specific approach. These products navigate the balance between educating a funder and motivating a researcher.

Other field-building tools that help build trust and legitimacy include:

Clear identity, vision, and unifying concept to attract attention and resources necessary for an early field to gain traction. Early field-builders should spend time answering: What is this field about, and why does it matter? A crisp answer will enable the growth of talent and funding.

Strategic, accessible, balanced framing with attention to exit ramps, stage gates, and risk evaluation. Focus on what is needed to understand a problem or idea rather than advocating for its success. Distinctions can be made between topics that are controversial and those that are just difficult to communicate (e.g. because of complexity).²¹

Engaged, credible advisors who actively help shape the early field and act as luminaries for the broader community as the field grows and evolves.

Field catalysts and connectors to generate momentum among funders, researchers, and institutions. Proactive field matchmaking – via a designated field coordinator or host organization – is rare in academia, which tends to be decentralized, but it can be the “secret sauce” to reach critical mass.

Credible artifacts such as peer-reviewed papers, roadmaps, articles, or blogs. In early fields there is high value in having these published by respected academics or organizations, and they can be particularly powerful if co-created with a team of credible experts.

Independent analyses and reports from established scientific bodies (e.g., IPCC, National Academies, U.S. Government Accountability Office) to ground early work in credible, structured evaluation.

Durable, equitable, and open funding to activate a diversity of actors and perspectives. Avoid forming a “club” of select actors where there may be hubris or siloing that limits transformative thinking.

Case Study:

Cascade Climate

Cascade Climate, 22 founded in 2023, is a philanthropy-backed nonprofit propelling emerging climate solutions from the margins to the mainstream, with a focus on durable carbon removal and super pollutant mitigation. The organization orchestrates catalytic interventions across science, markets, and policy to overcome bottlenecks and trigger self-reinforcing cycles of policy and industry action at scale. Their work in enhanced rock weathering (ERW), a promising agronomic approach that removes atmospheric carbon dioxide, demonstrates how connective tissue nurtures an emerging scientific field.

The emerging field of ERW faced two common issues: commercialization without common standards and a dearth of data from large-scale trials. These manifested as an early risk of fragmented quality tiers in commercial activity, and a set of open scientific questions that academic researchers lacked the data to answer.

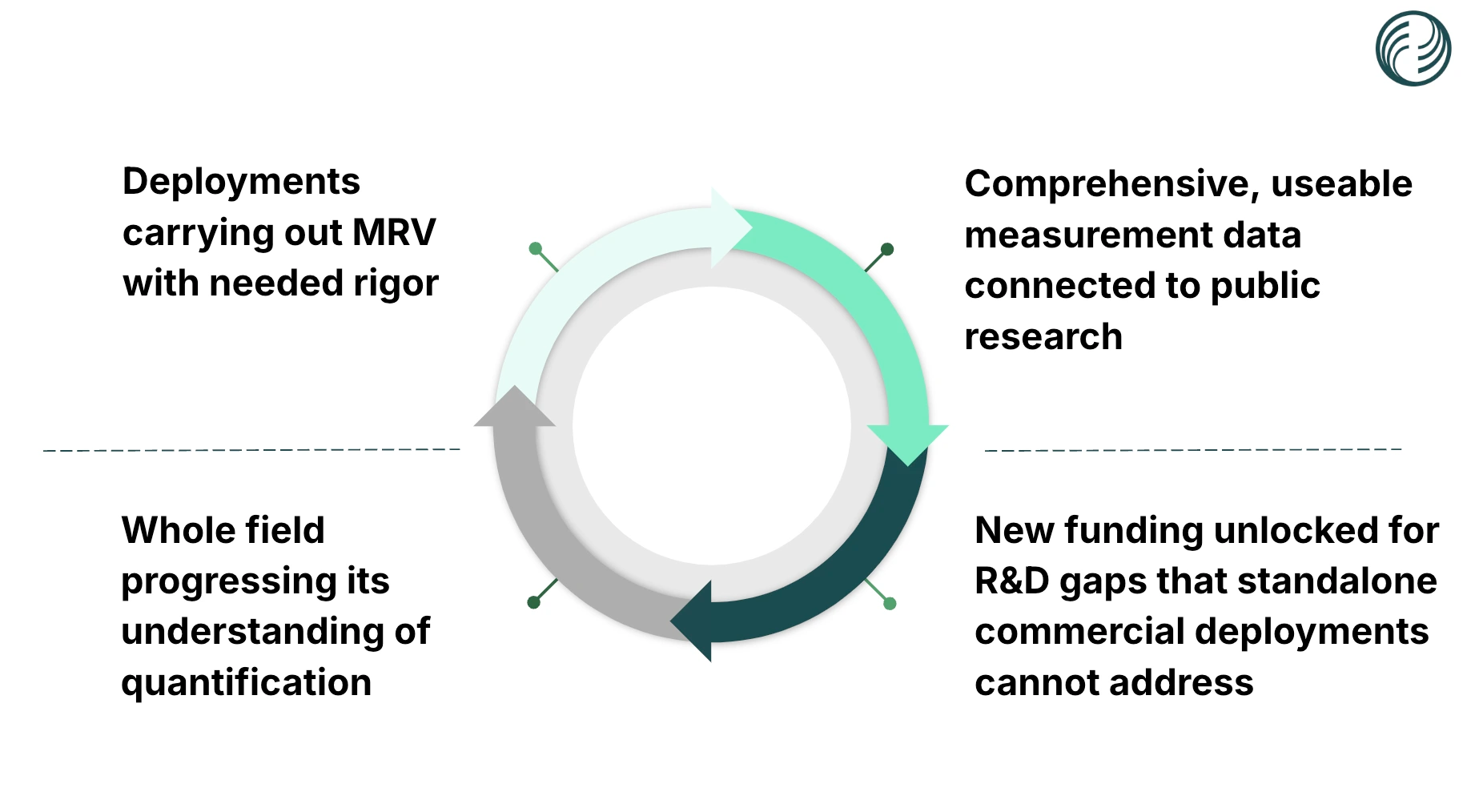

Cascade’s field-building strategy tackled these issues via the concept of deployment-led learning, a virtuous cycle connecting commercial deployments with research. First, commercial deployments are designed to maximize scientific learning, followed by data-sharing to enable academic research. Then, research findings unlock additional funding, which advances the entire field’s scientific understanding. This enables better commercial deployments, thereby renewing the cycle.

To enable deployment-led learning, Cascade’s first initiative was a shared framework for quantifying carbon removal in ERW deployments, to ensure a common core across commercial practices. To develop this framework, Cascade created and led a 10-month, multi-stakeholder process including academic scientists, commercial practitioners, and not-for-profit organizations. Cascade also worked with buyers and registries to ensure that learnings from the framework informed commercial practices. As a result, commercial activity in ERW has a common foundation that builds credibility while simultaneously being transparent about open scientific questions. Cascade also launched a data-sharing system, which allows researchers to access commercial ERW data while protecting commercial interests. Together, the shared quantification framework and the data-sharing system provide the connective tissue necessary for the deployment-led learning cycle.

Cascade Climate’s field-building strategy for ERW is centered on the cycle of deployment-led learning, whereby a foundation of trust and transparency encourages scientific learning and consistently rigorous deployment.

Resources

Creating, building, and sustaining a field requires different types of resources, which evolve as the field develops. At the latency stage, funding is the primary resource that enables growth. Early funding must be responsive to a “dual lens” perspective where there is focus both on the big picture state of the field and specific leverage points embedded within the field that can accelerate or unlock field progress.⁹ While not always possible, analogous work exploring social movements has identified the importance of committing to the long term, where “funding the work over an extended period (often at least a decade) enables the deep relationship building that powers field-based change and allows for the nonlinear progress that defines nearly every field success story.”² Support from the Rockefeller Foundation for oceanographic research starting in the early 1900s provides an example of the tremendous impact that can be realized by sustained field-based funding, establishing the field of oceanography and its most prestigious institutions including the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Scripps Institution of Oceanography.²³ Efforts in new, unestablished fields often struggle under common or traditional grantmaking processes, and benefit from application of creative funding mechanisms that are risk-tolerant and structured to unlock research that is unlikely to get support elsewhere. Funding for these efforts can flow from different sources, including philanthropic foundations or philanthropic-backed NGOs.

Effective field building funding mechanisms include:

Targeted closed funding: This mechanism refers to the selection and funding, without open solicitation, of researchers with specific expertise to address specific topics. During early field building, while a body of experts is being assembled and a shared knowledge base is being established, this person-focused approach can effectively engage field leaders and accelerate early advancements to understand if “there is a there there.” Closed funding can also be effective during later stages of field creation and growth, though should be approached carefully to ensure that determinations are made with due diligence, credibility, and are not biased by a funder “blind spot.”

Open solicitations: Many traditional funding sources (e.g. governments) rely on open solicitations to ensure equitable award of research funding to the highest quality applicants. There are many different ways to structure open solicitations and they often require well-defined eligibility criteria, peer review, and advisory or panel oversight. The quality and quantity of applications often increases as the field becomes more established, providing an opportunity to strategically structure sequential open solicitations to maximize impact from limited resources. For emerging fields, this can be a powerful mechanism for increasing awareness, engagement, and attracting new talent. As a robust, traditional approach, open solicitations can signal credibility to a broader community and temper controversy by reducing bias.

Fellowships: Emerging fields benefit from “top of funnel” talent development, which can include funding to activate early-career interest and engagement, as well as short-term support to engage later career talent that may lack the funding to pursue a big idea outside of their immediate area of expertise. Fellowship funding can be an effective, relatively low-cost mechanism to both identify talent that may otherwise be hidden and stimulate involvement in a topic that may otherwise be inaccessible. Fellowships can also be applied to expand networks, particularly for cross-pollination of expertise from adjacent fields enabling fellows to serve as ambassadors between two communities. Fellowships can take many different shapes; as one example, Astera runs a one-year residency program, supporting exploration of important scientific problems.²⁴

Mentorship exchanges: Talent development can be activated by pairing pioneers of an emerging field with seasoned mentors from established fields who have previously scaled new areas (e.g., an internet pioneer guiding a nascent quantum computing community on ecosystem building). Fields often stagnate in early years due to insularity; a controlled infusion of outside perspectives and skills can break that logjam. There is opportunity for institutions and funders to experiment with grants that require an interdisciplinary team or the inclusion of a newcomer from a different field to ensure strategic infusion of mentors.

Prize challenges and competitions: While there is limited quantitative empirical data on the impact of prizes on innovation,²⁵ there may be opportunities for a bold funding bet or challenge prize to leapfrog field development. Bold funding bets, if strategically placed, signal that a field is worth investing in and creates sustaining assets (e.g. labs, institutes, large datasets). Similarly, prize competitions can rally cross-disciplinary talent from unexpected places to tackle core challenges. Such prizes have catalyzed fields in technology and social arenas, and could do the same in science by focusing minds on high impact breakthroughs. These strategies must be designed to be catalytic, creating opportunity for follow-on investment and a community of solvers, not just one-off wins.

Focused Research Organizations (FROs): Pioneered by Convergent Research, FROs are recommended as a new type of organization suited for ambitious projects that are “bigger than an academic lab can undertake, more coordinated than a loose consortium or themed department, and not directly profitable.”²⁶ ²⁷ Renaissance Philanthropy has explored the role that this type of organization can play to advance mid-scale scientific investments that are accelerative for scientific innovation.²⁸

Case Study:

Spark Climate Solutions

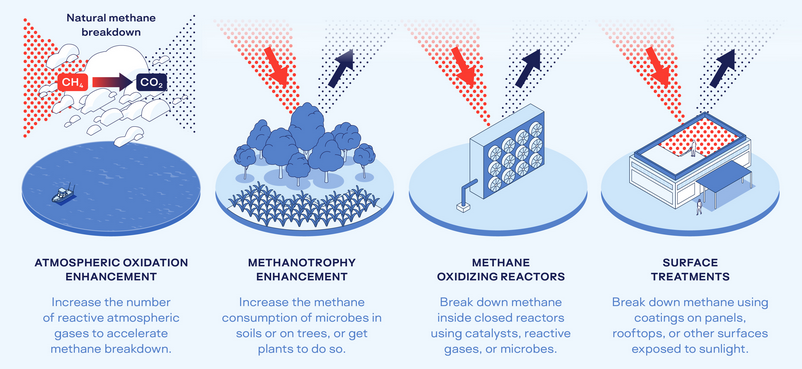

A philanthropically funded nonprofit, Spark Climate Solutions works with scientists, policy makers, and peer organizations, to identify and mitigate sources of unmanaged climate risk. 29 As part of their portfolio, they serve as a catalyst for the emerging field of methane removal, a potential suite of climate intervention approaches to help counteract rising methane emissions – including from climate feedbacks – that are difficult to abate.

Spark implemented a research funding program in this emerging space to kickstart early research that struggled to get traction from traditional government funding sources. As a field intermediary, they used a mixed-model approach for regranting of philanthropic funds, with targeted closed funding directly to grantees as well as running open solicitations.

The targeted closed funding served to stimulate an initial cohort of grantees and was quickly followed by open solicitations that served to grow the community of practitioners and establish the emerging field as credible and inclusive. In parallel, Spark led a community-driven roadmapping effort to identify priority research questions, 30 which informed the content of the funding program solicitations. These efforts were structured to create momentum, positioning the field to transition from being solely funded through Spark to being supported by a broader funding landscape.

Spark Climate Solutions applied creative funding mechanisms to catalyze a nascent, controversial field.

Recommendations

For philanthropists

Provide catalytic, patient capital: Embrace funding strategies that others can’t or won’t pursue. Early-stage scientific fields often need high-risk seed funding to explore unproven ideas and patient long-term capital to build out infrastructure. As the Science Philanthropy Alliance observes, many transformative research ideas are “absolutely impossible to fund except via philanthropy” in their early days.³¹

Fund convenings and community-building: Allocate budget specifically for field-building events and platforms. Often what nascent fields need most is simply to get all the interested minds in the same room (physical or virtual). Philanthropists can accelerate this by sponsoring workshops, retreats, or conference sessions that bring together pioneers from multiple disciplines. Early cross-pollination has outsized effects: it helps researchers find collaborators, agree on common language, and avoid duplicate efforts.

Invest in field infrastructure: Think beyond projects and fund the shared infrastructure that allows a field to function. This includes tangible resources like databases or instrumentation facilities, as well as intangible ones like journals, professional societies, and training programs. Early philanthropy can fill infrastructure gaps that are unlikely to receive funding from academia (unestablished intellectual value) or industry (lack of profits). These investments are true force-multipliers.

Use influence to broker support: Philanthropists can leverage their unique position to bring in other supporters once the field shows progress. Act as a field champion in broader circles.

For scientists

Seize incentives for field entry: Actively seek out programs that lower the barrier for entry. Many institutions and funders (especially new philanthropic initiatives) are beginning to offer grants, prizes, or fellowships specifically for cross-disciplinary exploration.

Build networks, not just papers: In a new field, who you know can be as important as what you know. Take the initiative to connect with others interested in the field and form networks from the onset. By actively co-creating the community there is opportunity to identify and pursue novel ideas that may otherwise be inaccessible.

Be a systems thinker: What is the “big vision” of this field, and how does my work contribute to it? Don’t assume everyone knows why the emerging field matters; practice articulating its importance to different audiences (other scientists, funders, the public). This can be done through reviews, perspective pieces, or informal interactions. Paint both the picture of the problem to be solved or the new frontier to address it.

Proactively seek cross-disciplinary mentors: If the field is interdisciplinary (as most new fields are), identify a mentor or collaborator from each relevant domain; they will help avoid naive mistakes and integrate methods correctly. Don’t limit mentorship to senior academics; peer mentorship is incredibly valuable too. Share techniques and known pitfalls with each other to flatten the learning curve. Likewise, for senior scientists, be generous with mentorship to junior entrants – it will strengthen the field’s human capital. Advocate for (or organize) cross-training opportunities.

How we can help

Help design and support events to catalyze emerging fields and grow the talent pipeline.

Help researchers determine if their idea may contribute to an existing emerging field or be the kernel of a new emerging field.

Advise on or sponsor roadmap development.

Provide guidance on funding program design.

Connect to other field builders to learn from their successes/failures.

Authors

Katrine Gorham (Spark Climate Solutions), Pritha Ghosh (Cascade Climate)

Acknowledgements

Katrine Gorham (Spark Climate Solutions), Pritha Ghosh (Cascade Climate)

Endnotes

The Bridgespan Group (2020). Field Building for Population-Level Change. https://www.bridgespan.org/getmedia/6d7adede-31e8-4a7b-ab87-3a4851a8abac/field-building-for-population-level-change-march-2020.pdf

The Foundation Center (2004). Practice Matters: The Improving Philanthropy Project, Ideas in Philanthropic Field Building. https://www.issuelab.org/resources/6478/6478.pdf

ORS Impact (2020). Not Always Movements, Going Deeper: Building a Field. https://www.orsimpact.com/DirectoryAttachments/6242020_41543_949_Not_Always_Movements_Field_Building.pdf

Spark Policy Institute (2017). What it Takes to Build or Bend a Field of Practice. https://kresge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/what_it_takes_to_build_or_bend_a_field_of_practice.pdf

The Bridgespan Group (2009). The Strong Field Framework. https://www.bridgespan.org/getmedia/16a72306-0675-4abd-9439-fbf6c0373e9b/strong-field-framework.pdf

Nielsen, M. and Qiu, K. (2022). A Vision of Metascience: An Engine of Improvement for the Social Processes of Science. https://scienceplusplus.org/metascience/#metascience-as-an-imaginative-design-practice

Muehlhauser, L. (2017). Some Case Studies in Early Field Growth. https://coefficientgiving.org/research/some-case-studies-in-early-field-growth/

Hübsch, Sarah (2022). Master Thesis, Utrecht University. How philanthropic foundations act as field-builders influencing justice discourse in land conservation. https://studenttheses.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12932/41826/SH_FinalMasterThesis_29.06.2022.pdf?sequence=1

The Bridgespan Group (2024). Measurement, Evaluation, and Learning: A Guide for Field Catalysts. https://www.bridgespan.org/getmedia/e6226561-b665-42d4-8c2b-bbc3677b64f7/measurement-evaluation-and-learning-guide-for-field-catalysts.pdf

Gilliam, Eric. Personal communication (March 5, 2025).

Flagship Pioneering, Moderna Timeline. https://www.flagshippioneering.com/timelines/moderna-timeline

Temple, J. A startup says it’s begun releasing particles into the atmosphere, in an effort to tweak the climate. MIT Technology Review (2022). https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/12/24/1066041/a-startup-says-its-begun-releasing-particles-into-the-atmosphere-in-an-effort-to-tweak-the-climate/

Baaden P., et al. On the emergence of interdisciplinary scientific fields: (how) does it relate to science convergence? Research Policy (2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733324000751

The Time Initiative. https://www.timeinitiative.org/

CDRXIV: Preprints and Data for Carbon Dioxide Removal. https://cdrxiv.org/

ARC: Advanced Research for Climate Emergencies. https://arc.renaissancephilanthropy.org/

CEF: Climate Emergencies Forum. https://www.renaissancephilanthropy.org/uk-horizons-cef

Hill, R., et al. The pivot penalty in research. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09048-1

Schmidt Science Polymaths. https://www.schmidtsciences.org/schmidt-science-polymaths/

Marblestone, Adam (2025). A Beginner’s Guide to Scientific Roadmapping. https://convergentresearch.substack.com/p/scientific-roadmapping

Elliott, Joshua. Personal communication (February 20, 2025).

Cascade Climate. https://cascadeclimate.org/

Rockefeller Archive Center (2020). Philanthropy and Oceanography: An Episode in Field-Building. https://resource.rockarch.org/story/philanthropy-and-oceanography-an-episode-in-field-building

Astera. https://astera.org/residency/

Rethink Priorities (2022). How effective are prizes at spurring innovation? https://rethinkpriorities.org/research-area/how-effective-are-prizes-at-spurring-innovation/

Convergent Research. https://www.convergentresearch.org/

Marblestone, A., et al. Unblock research bottlenecks with non-profit start-ups. Nature (2022). https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00018-5

Renaissance Philanthropy. (2024). Playbooks: Mid-scale science. https://renaissancephilanthropy.org/playbooks/mid-scale-science/

Spark Climate Solutions. https://www.sparkclimate.org/

Gorham, K.A., et al. Opinion: A research roadmap for exploring atmospheric methane removal via iron salt aerosol. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (2024). https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/24/5659/2024/acp-24-5659-2024.html

Science Philanthropy Alliance. https://sciencephilanthropyalliance.org/