Chimaera Fund

Activating Earth’s hydrogen generator.

About

The Chimaera Fund aims to responsibly and rapidly scale geologic hydrogen – the first new primary energy source discovered in 80 years. Drawing from the playbooks that scaled other subsurface revolutions like shale gas and geothermal energy, we invest in open-access field demonstrations and advise national and subnational governments on effective policy designs to unlock the industry by 2030.

Why GeoH2?

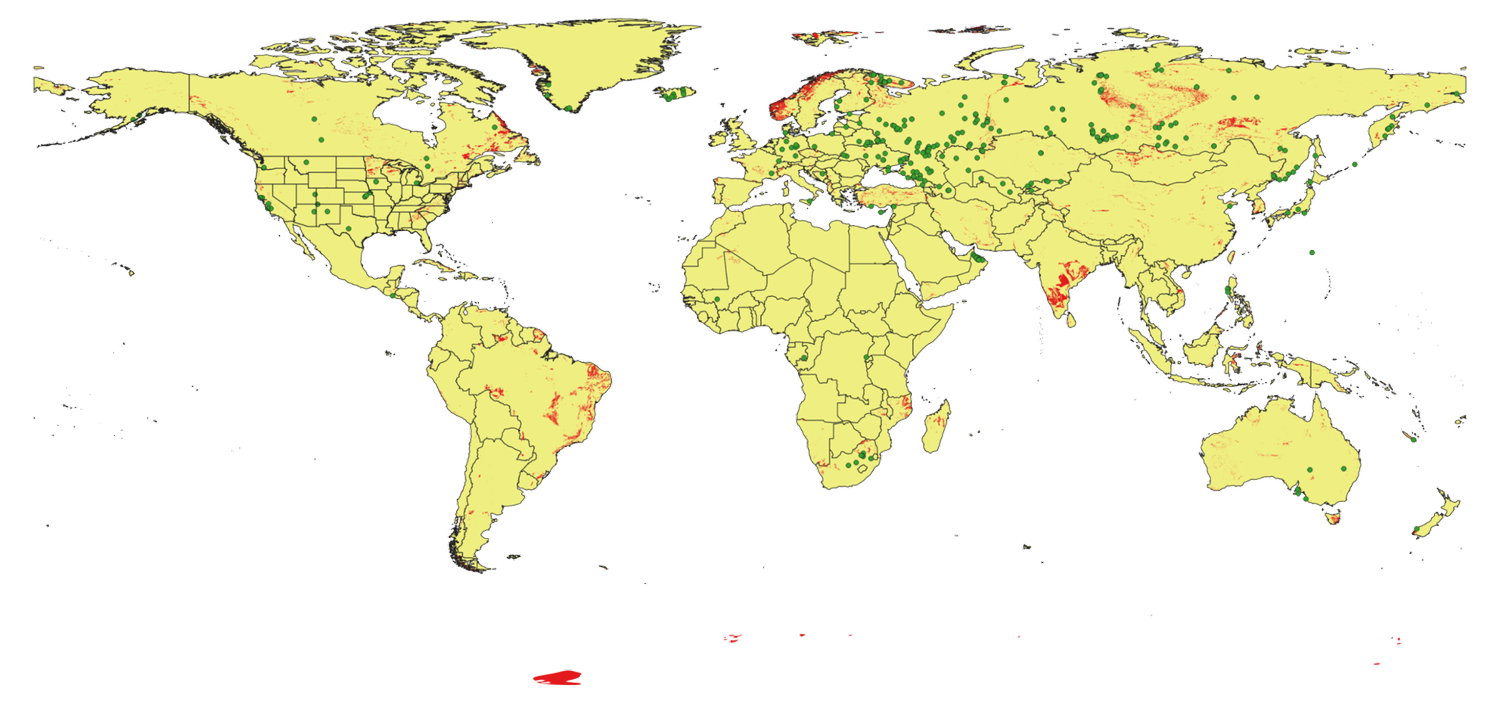

Formed from natural geologic processes like the chemical interaction between water and iron-rich rocks, geologic hydrogen (geoH₂) is a newly discovered resource that geoscientists estimate may be much greater than the energy content of known natural gas reserves.

By mining instead of manufacturing hydrogen, geoH₂ represents humanity’s first opportunity to generate net-positive energy from the universe’s most abundant element.

It has the potential to produce $0.50–$1.50 per kilogram of clean hydrogen nearly two decades earlier than our current trajectory, creating a near-term solution for 30-40% of global emissions without a scalable answer.

At that price point, geoH₂ would present a step change for our global economic and energy security, decarbonizing while lowering prices for fundamental goods and services such as steel, jet fuels, fertilizer, shipping and trucking, mining, and power generation.

The following sectoral assessments are high-level, order-of-magnitude estimates based on current assumptions and should be interpreted as directional rather than definitive.

-

Steel accounts for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Clean hydrogen has long been viewed as pivotal to decarbonizing the steel industry, with cost seen as a primary constraint. With current steel production concentrated in China, India, the U.S., Japan, Korea, Brazil, and Turkey – countries suspected to have high amounts of geoH₂ – we see a unique opportunity to avoid systemic emissions lock-in from upcoming industry expansions while reducing the cost of steel production, if $1 per kg of clean hydrogen can be proven in the next 5-7 years.

-

The aviation industry represents 3% of greenhouse gas emissions, almost exclusively caused by the burning of jet fuels. Hydrogen is a fundamental feedstock to producing clean jet fuels. Recent modeling indicates geoH₂ could quadruple demand for sustainable aviation fuels and potentially other feedstock sources like CO₂.

-

High-temperature heat processes represent a large share of emissions within certain industrial sectors, such as cement, glass, and ceramics, which together represent roughly 7-8% of global emissions.

Roughly 30-40% of cement’s emissions come from heating materials at 1,000-1,600°C to form clinker (about 3.2% of global emissions), while roughly 75-85% of energy requirements in glass and brick kilns come from similar high-temperature processes.

The opportunity goes beyond emissions, as in many places these processes contribute significantly to air quality. In India, for example, brick-kilns are estimated to be responsible for two-thirds of industrial black carbon pollution.

If low-cost clean hydrogen is available, it serves as a drop-in combustion fuel in many kiln and furnace designs, making it one of the few broadly applicable decarbonization levers that can scale through retrofits rather than full plant rebuilds. -

The chemicals industry represents 4-6% of greenhouse gas emissions and it runs mostly on fossil-based hydrogen. At $1 per kg, geoH₂ becomes a rare drop-in option that can decarbonize without needing to rebuild chemical plants. Ammonia, for example, represents 1% of greenhouse gas emissions and is produced by synthesizing nitrogen with hydrogen – a process dependent on the price of natural gas and entirely replaceable by geoH₂.

-

Maritime shipping produces approximately 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and for long-haul routes where direct electrification is often impractical, hydrogen-based alternative fuels could become a leading solution.

GeoH₂ could materially narrow the green fuel-cost premium for these alternative fuels, while eliminating nearly all CO₂ and SOx emissions, enabling near-term compliance with the International Maritime Organization’s interim target of 40% lower carbon intensity by 2030.

-

Despite a small percentage of the on-road vehicle population, long-haul heavy-duty trucks are responsible for about 5% of global CO₂ emissions. Hydrogen fuel-cell trucks can offer zero tailpipe emissions with hundreds of kilometers of range and refueling times often estimated in the ~10–20 minute range under suitable station conditions, as early field trials report.

-

The mining sector is often estimated to account for about 4–7% of greenhouse gas emissions, with a large share driven by diesel use in mobile equipment – especially haul trucks – and energy used for grinding and ore processing (typically electricity plus site fuels). Because geologic hydrogen is commonly generated through ultramafic rocks, and many critical mineral systems are associated with mafic/ultramafic settings, there is a plausible opportunity set where hydrogen production and mining operations could overlap geographically – particularly valuable for remote sites that need local power and fuel.

-

Unlike current methods of producing hydrogen, which require significant energy input and therefore serve as energy carriers, geoH₂ produces more energy than it requires. As a new primary energy source, geoH₂ could supply baseload firming power to zero-water, zero-emissions data centers as well as support remote communities switching from diesel generators. Additionally, companies are evaluating the use of ammonia produced from clean hydrogen as a partial replacement for coal in power plants to reduce power sector emissions.

Opportunity

From hydrocarbons to critical minerals, modern civilization has always been powered by the Earth. But our ability to access the subsurface has long outpaced our ability to understand it. The fundamental constraint is that wells are expensive and subsurface science depends on drilling them.

That constraint has meant that, for most of history, only industry has had the capital to generate subsurface data – and it has seldom, if ever, shared it. The rare moments when subsurface data has been shared have sparked subsurface revolutions.

Shale gas had been known for more than a century as a niche, limited resource. In the 1970s, the Eastern Gas Shales Project (EGSP) assembled industry, academia, and government around dozens of demonstration wells, validating the foundation for the private sector to leverage horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing, and shale recovery. Within two decades, shale boomed.

Geothermal offers a more recent parallel. America generated electricity at The Geysers as early as the 1920s, but again the industry was viewed as niche and highly localized. In 2021, the open-science demonstration testbed Utah FORGE drilled its first deep, deviated wells in Milford, Utah. This year and within the same county, the world’s largest next-generation geothermal project is set to deliver power to the grid with the rest of the industry picking up steam.

Geologic hydrogen has powered the village of Bourakébougou in western Mali for more than a decade. The question now is whether this resource can be produced at industrial scale – reliably, safely, and affordably. More than $1 billion has already flowed to 100+ geoH₂ startups to answer that question. But markets will reliably underfund the highest-leverage, pre-competitive investments – open-access demonstration wells, standardized workflows and data practices, and effective public policy – that can compress industry learning curves from centuries to years.

Initiatives

Our team has identified three program areas where time-bound, targeted philanthropic investment can deliver outsized impact for the entire field, accelerating learning curves, improving safety, and helping determine where geologic hydrogen can become a durable, cost-competitive part of the global energy system.

Catalyst: Multiply the industry’s learning-by-doing effect by sourcing and supporting open-science field demonstration partnerships.

Current Initiative: Site Access Challenge. Launched in November 2025 with industry first-mover Hyterra, this grants competition will be the first time in history researchers can access commercial hydrogen wells and publish results openly. You can access the Request for Proposals here.

Future Initiative: Demonstration Challenge Grants. We are evaluating opportunities to convene buyers and producers of geologic hydrogen in a major demonstration challenge that seeds a future commercial project.

Atlas: Accumulate and synthesize high-impact datasets and foundational knowledge to promote evidence-based progress and industry best practices.

Future Initiative: Common Core Library. We are evaluating opportunities to support rapid testing on high quality core samples in 10+ U.S. regions, systematically raising the “common core” evidence floor and standardizing workflows that improve learning translation from future pilots.

Forge: Advise national and subnational governments in building a safe, credible geoH₂ industry by aligning regulations and incentives — such as the $100B+ in global hydrogen subsidies — towards subsurface exploration and deployment.

Current Initiative: In the State of Michigan, we are supporting the implementation of the Michigan Executive Directive on Geologic Hydrogen – the first statewide initiative of its kind – and serve as a member of the Michigan Council on Future Mobility and Electrification’s Hydrogen Action Team.

Future Initiative: State Policy Fellows Program. We are evaluating placing fellows in key U.S. state government positions to take advantage of their subsurface resource opportunities, from critical minerals and geothermal to geologic hydrogen.

Director

-

Ishan Sharma

Advisory Board

-

Dr. Douglas Wicks

Strategic Director, ASCENT Japan and Former ARPA-E Geologic Hydrogen Program Director

-

Dr. Alexis Templeton

Professor of Geochemistry and Geobiology, University of Colorado Boulder

-

Dr. Geoffrey Ellis

Petroleum Geochemist and Geologic Hydrogen Lead, U.S. Geological Survey

-

Dr. Mark Myers

Commissioner at the U.S. Arctic Commission and Former Director of the U.S. Geological Survey

-

Dr. Allegra Hosford Scheirer

Managing Director of the Stanford Geologic Hydrogen Program

-

Doug Hollett

Originator of the Utah FORGE geothermal test site and Former DOE Senior Official

-

Morten Stahl

Founding Partner, Natural Hydrogen Ventures

Our Partners

With thanks for generous contributions from private individuals.

Latest News